Rewilding

Rewilding

Feral is a delicious word. It means to be ‘in a wild state, especially after escape from captivity or domestication.’ For those of us living in the the modern world, feral is something we yearn for, and deserve.

George Monbiot: Feral

It’s a common enough word, but I bumped into it, like all truly momentous things, by pure serendipity. A talk by the writer, and environmentalist, George Monbiot, tuned into my radio one afternoon. Feral is the title of his book, but the subject – and what made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up and my car career into the layby – is rewilding.

His story begins in Yellowstone. In 1995 a small number of wolves, having been hunted to near extinction, were reintroduced to the National Park. For the past 70 years, leading up to that point, the deer, without a natural predator, had devastated the landscape, reducing the vegetation to almost nothing. Despite many very smart human’s best efforts to intervene, the situation was out of control.

The Wolves of Yellowstone

But the wolves had an immediate impact: they killed some deer, of course, but that wasn’t the main thing. Their greatest effect was that they changed the behaviour of the deer. The deer stopped going to certain areas where they knew they would be at their most vulnerable. As they did so those places immediately started to regenerate: devastated valleys became forests again; birds, and other small animals, returned – the ecosystem, in an ecological blink of an eye, began to flourish.

But something even more amazing happened too: the wolves changed the behaviour of the rivers. As the forests grew they stabilized the banks of the rivers, fixing their course and providing better habitats and a more balanced ecosystem as a whole. Unbelievably, the reintroduction of a single species changed the physical geography of the entire 3,500 square mile Yellowstone National Park.

Gaia Hypothesis

Except, of course, it’s not unbelievable at all. The Gaia hypothesis, put forward by James Lovelock almost 50 years ago, proposes that the earth is a self-regulating system. Everything is connected. Every insect, flower, wolf, deer and human effects, and sustains, the conditions for life on Earth.

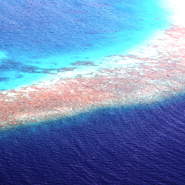

This idea underpins the proposition of rewilding. If we step back, nature will self-regulate. And the evidence is everywhere we care to look: in the effect of whales on krill populations in the southern oceans, in the regeneration of Scottish forests in Dundreggan by the Trees for Life foundation, even by the return of trout to the River Wandle in south London. The planet will heal itself.

Rewilding

But, surprisingly, this is contrary to much contemporary conservation, which – with the best of intentions – seeks to reconstitute the earth to some prior state: to maintain this meadow, to restore this heath, to protect this marshland. But nature doesn’t work like that. Nature ebbs and flows, nature changes and reacts. Rewilding isn’t about preservation; it’s about letting go. Tear down the fences, seal up the ditches, replace what you have removed, and then walk away.

In framing our ecological challenges in a positive, and future focused way, rewilding is unique. We can’t restore what was, but perhaps something new can begin again. Rewilding tells us that we needn’t just despair; if we trust in the inherent systems of the earth there is hope still.

And perhaps there’s hope for us too, which brings me back to the word feral. “We have evolved in a world of horns and tusks and fangs and claws,” Monbiot says. “We still possess the fear, and the courage, and the aggression, required to navigate those times. But in our comfortable, safe, crowded lands we have few opportunities to exercise them.”

In his book, Monbiot is searching for a deeper connection to that animal inside of us. He doesn’t want to do away with civilization. He rejects primitivism. But he seeks a balance, a rawer more adventurous life – one where he is able to stop crawling the walls and connect instead more easily with the wildness around him, and inside him. He envisions a world where there are Serengetis on our doorstep, where we allow space for nature to flourish unconstrained by human hands, where the comfort of modernity assists human life, but doesn’t control it.

George Monbiot is one of my favourite writers and a true ecological pioneer. Find out more about his book, and other work at Monbiot.com

This article originally appeared in Positive News, the constructive journalism magazine. They’re one of my favourite publications to write for, please check them out if you can.

Comments...